Reg X and DFA

Front Notes

- The Theory of Computer Science is very abstract, and to be honest, you won’t use it directly in most programming roles. However, if you’re interested in compiler design, you should take this subject seriously. I found the MIT open lectures by Michael Sipser and the Easy Theory YouTube channel incredibly helpful for understanding the course material. Most importantly, avoid Eberly at all costs.

What are Regular Expressions?

- A regular expression (regex) is a sequence of characters that defines a search pattern within text. Regexes are incredibly powerful for finding, matching, replacing, and extracting specific pieces of information from larger strings.

Why Learn Regex?

- Text Manipulation: Regex makes complex text processing tasks a breeze.

- Efficiency: A single regex pattern can replace lines of traditional code.

- Data Validation: Ensure user input (like emails or phone numbers) follow the correct format.

- Web Scraping: Extract targeted data from websites.

- Code Cleanup: Refactor code and find patterns.

Basic Building Blocks

- Literals: The simplest regex elements are plain characters.

- Example: “cat” matches the literal word “cat”.

- Metacharacters: These have special meanings in regex.

- . (Period): Matches any single character (except newline, usually). Example: “c.t” matches “cat”, “cot”, “c#t”, etc.

- \d: Matches a single digit (0-9).

- \w: Matches a single word character (letter, number, or underscore).

- []: Character class. Matches any character inside the brackets. Example: “[abc]” matches “a”, “b”, or “c”.

- ^: Matches the beginning of a string or line. Example: “^Hello” matches “Hello World” but not “Some text Hello”

- $: Matches the end of a string or line Example: “World$” matches “Hello World” but not “Hello World Again”

- Quantifiers: Specify how many times an element should repeat.

- *: Zero or more times. Example: “colou*r” matches “color” and “colour”.

- +: One or more times. Example: “\d+” matches “123” but not “”.

- ?: Zero or one time. Example: “Nov(ember)?” matches “Nov” and “November”.

- {n}: Exactly ‘n’ times. Example: “\d{3}” matches three-digit numbers.

- {n,m}: At least ‘n’ times, at most ‘m’ times.

Example: Email Validation

A basic email regex:

/^[\w-\.]+@([\w-]+\.)+[\w-]{2,4}$/

String Operations vs. Language Operations

- String Operations:

- Find Matches: Regex can check if a pattern exists within a string.

- Extract Matches: Isolate and capture specific parts of a string.

- Replace Matches: Substitute text with new content based on the regex pattern.

- Split String: Divide a string into substrings using a regex as the delimiter.

- Language Operations:

- Groups ( ): Used for capturing parts of a match. Example: “(\d{3})-(\d{3})-(\d{4})” captures three number groups in a phone number.

-

**Alternation ( ):** A sort of “or” operator. Example: “cat dog” matches either “cat” or “dog”.

Note on Notation

You’ll sometimes see the union symbol (U) used in set theory in the context of regular expressions. The ‘+’ symbol often serves the same purpose.

Tools and Practice

- Websites:

- regex101: https://regex101.com/ (Test, build, and debug regex with explanations)

- RegExr: https://regexr.com/ (Learn and experiment interactively)

- Most programming languages (Python, JavaScript, Java, etc.) support regex.

What are Finite Automata?

- A Finite Automaton (FA) is a simple mathematical model of a machine that reads input symbols and transitions between states based on those symbols.

- FAs are used to recognize patterns within input strings.

- There are two main types:

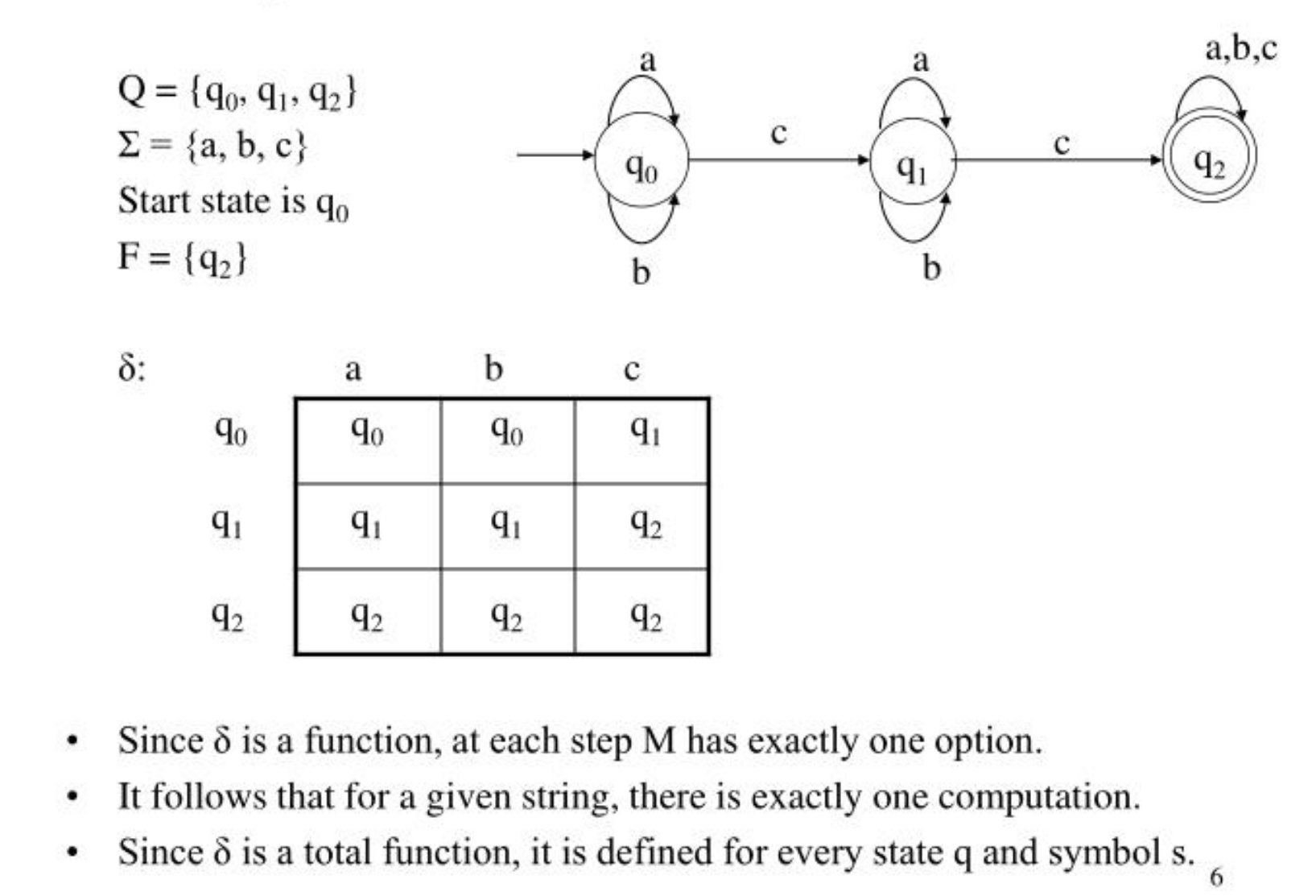

- Deterministic Finite Automata (DFA): For each state and input symbol, there is exactly one possible next state.

- Nondeterministic Finite Automata (NFA): For each state and input symbol, there can be multiple next states, or even no transitions at all.

Components of a DFA

- States (Q): Represented by circles.

- Input Alphabet (Σ): The set of valid symbols.

- Transition Function (δ): Defines how the DFA moves from one state to another based on input symbols (represented by arrows).

- Start State (q0): The initial state (usually has an arrow pointing to it from nowhere).

- Accept State(s) (F): If the machine ends in an accept state after reading the input string, the string is accepted (usually marked with a double circle).

Example: DFA Recognizing Strings Ending in “01”

- States: {q0, q1, q2}

- Alphabet: {0, 1}

- Start State: q0

- Accept State: q2

- Transition Function: See the diagram below

Regular Expressions and Languages

- Regular Expression: A pattern defining a set of strings.

- Language: The set of strings accepted by a DFA or described by a regular expression.

For the Above DFA:

- Regular Expression: (0+1)*01

- Language: All strings over the alphabet {0, 1} that end in “01”.

How DFAs Work

- Start in the initial state.

- Read input symbols one by one.

- Follow transitions based on the current state and input symbol.

- If the input is completely read and the DFA is in an accept state, the string is accepted. Otherwise, it’s rejected.

Key Points

- DFAs and Regular Expressions are closely related. Every regular expression has an equivalent DFA, and vice versa

- NFAs are more flexible, but both can recognize the same class of languages (regular languages).

Some exercise Questions

1. (AB)

The language (AB) is formed by concatenating each string in (A) with each string in (B). This results in all possible combinations where an element from (A) precedes an element from (B).

- For (1 \in A):

- Concatenating with (11 \in B): (111)

- Concatenating with (10 \in B): (110)

- Concatenating with (\lambda \in B): (1)

- For (00 \in A):

- Concatenating with (11 \in B): (0011)

- Concatenating with (10 \in B): (0010)

- Concatenating with (\lambda \in B): (00)

So, (AB = {111, 110, 1, 0011, 0010, 00}).

2. (BA)

The language (BA) is formed by concatenating each string in (B) with each string in (A), effectively the opposite of (AB).

- For (11 \in B):

- Concatenating with (1 \in A): (111)

- Concatenating with (00 \in A): (1100)

- For (10 \in B):

- Concatenating with (1 \in A): (101)

- Concatenating with (00 \in A): (1000)

- For (\lambda \in B):

- Concatenating with (1 \in A): (1)

- Concatenating with (00 \in A): (00)

Thus, (BA = {111, 1100, 101, 1000, 1, 00}).

3. (B^2)

The language (B^2) is formed by concatenating each string in (B) with itself.

- (11) concatenated with (11): (1111)

- (11) concatenated with (10): (1110)

-

(11) concatenated with (\lambda): (11)

- (10) concatenated with (11): (1011)

- (10) concatenated with (10): (1010)

-

(10) concatenated with (\lambda): (10)

- (\lambda) concatenated with anything in (B) gives the elements of (B).

So, (B^2) includes elements like (1111, 1110, 11, 1011, 1010, 10), plus all elements of (B) because of the concatenation with (\lambda).

4. ((AB)^*)

The language ((AB)^) includes all strings that can be formed by taking the language (AB) and concatenating its elements any number of times, including the empty string ( \lambda ) (because any language to the power of () includes the empty string by definition of the Kleene Star operation).

This language is infinite and includes ( \lambda ), (111), (110), (1), (0011), (0010), (00), combinations of these strings with themselves and each other any number of times.

5. ((A \cup B)^*)

The language ((A \cup B)^*) is the set of all strings that can be formed by taking any combination of elements from (A) union (B) (which is all elements from both (A) and (B)), and concatenating them any number of times, including none (to include ( \lambda )).

Since (A \cup B = {1, 00, 11, 10, \lambda}), ((A \cup B)^*) is an infinite set that includes every possible string made up of (0)s and (1)s, including the empty string ( \lambda ), because you can concatenate any elements from (A \cup B) in any order, any number of times.

This explanation steps through the composition and interpretation of each language operation based on the initial sets (A) and (B). Each step builds on the understanding of how operations like concatenation, union, and the Kleene Star affect the formation of new languages from the original sets.

1. (A^* = (A^)^)

The Kleene Star operation (()) on a language (A) results in a language that includes all possible strings of zero or more concatenations of strings from (A), including the empty string (\lambda). Therefore, (A^) includes (\lambda), all strings in (A), all strings formed by concatenating one or more strings from (A), and so on.

When we apply the Kleene Star operation to (A^) itself to get ((A^)^), we are effectively allowing zero or more concatenations of strings from (A^), which already includes all possible concatenations of strings from (A) plus the empty string. Since (A^) includes every possible concatenation of elements from (A), including the empty string, applying the Kleene Star operation to it again doesn’t add any new strings to the language. Thus, ((A^)^) does not extend the set of strings beyond what is already included in (A^).

Hence, this statement is true: (A^* = (A^)^).

2. (A^+ = (A^+)^+)

The (+) operation, or Kleene Plus, on a language (A) results in a language that includes all possible strings of one or more concatenations of strings from (A), excluding the empty string (\lambda). (A^+) thus includes all strings in (A), all strings formed by concatenating two or more strings from (A), and so on.

Applying the (+) operation again to (A^+) to get ((A^+)^+) means looking for one or more concatenations of the strings already in (A^+), which itself represents one or more concatenations of strings from (A). Since (A^+) already encompasses all strings that could be formed by one or more concatenations of (A), further applying the (+) operation does not introduce any new elements that weren’t already included.

Therefore, this statement is true: (A^+ = (A^+)^+).

3. (A^+ = (A^+)^*)

Comparing (A^+) and ((A^+)^), the difference lies in the presence of the empty string (\lambda). (A^+) includes strings formed by one or more concatenations of (A), excluding (\lambda), while ((A^+)^) includes all the strings in (A^+) plus the empty string (\lambda), because the Kleene Star ((*)) operation allows for zero occurrences of its operand strings, which includes allowing for the empty string.

This distinction means that while (A^+) and ((A^+)^) contain all the same strings formed by concatenating elements of (A), ((A^+)^) additionally includes the empty string (\lambda), which (A^+) does not.

Thus, the statement (A^+ = (A^+)^) is false because ((A^+)^) includes (\lambda), whereas (A^+) does not.

Symbol Clarification

-

⊆ (Subset): This symbol is used to denote that one set is a subset of another set. When we say “A ⊆ B”, it means every element of set A is also an element of set B. It’s important to note that a set is considered a subset of itself, so A ⊆ A is always true. Additionally, this symbol allows for the possibility that the two sets are equal, meaning that A can be exactly the same as B.

-

∈ (Belong To): This symbol is used to indicate that a specific element is a member of a set. When we say “x ∈ A”, it means that the element x is contained within the set A. It focuses on individual elements being part of a larger set.